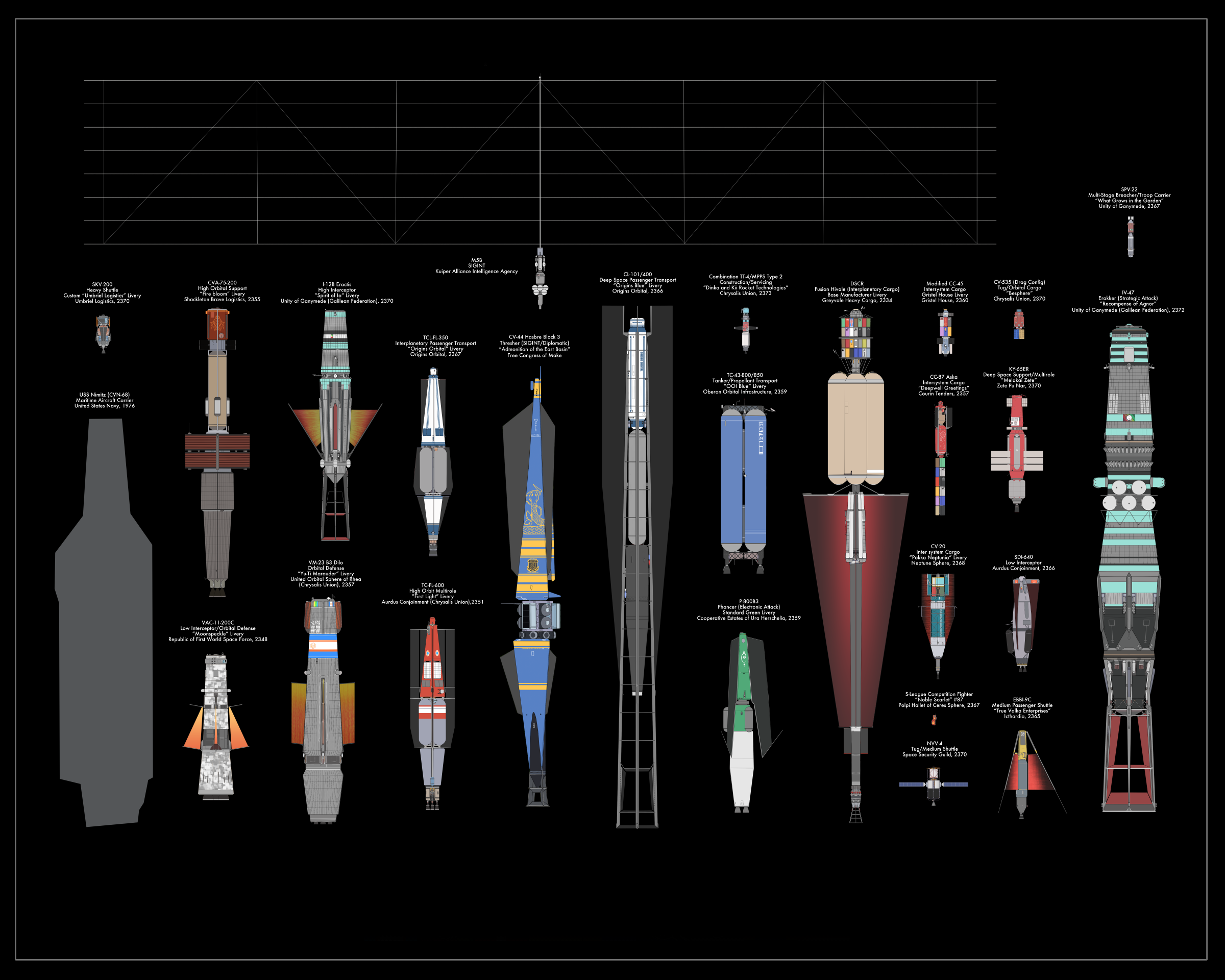

Spacecraft of Sol

A Lineage of Rocketry – A collection of spacecraft examples, 2334-2373

Space travel has come a long way in 400 years. Though spacecraft are infinitely more advanced than they were when the pre-impact Continentals landed on the Moon in the 1950s, the core principles still hold true. To go anywhere in space, one must change velocity. Even after hundreds of years, launching something out the back of a vehicle is still the best way to do that.

Chemical Propulsion

The Dirty Burn Regime

The fuel types that originally landed Continentals on Luna and Mars are still in use today. Kerosine, hydrogen, methane and oxygen are useful for situations where power density matters. Sometimes weirder propellants like iron, aluminum or silicon slurry substitute the traditional fuels in places where metals are more economical. The shuttles that ferry passengers and cargo from larger ships to orbitals rarely need a bigger kick than these fuels can provide. Their plumes are smaller, less damaging and non-radioactive, making them ideal for use in congested spaces. The fuels themselves are easily manufactured and readily available in quantity.

For the most part, the motors that utilize these fuels haven’t changed much over the centuries. Pumps feed liquid fuels and oxidizers to create a reaction that blasts out of a nozzle and pushes the whole thing forward. The technology has a very long, proven history and though they are somewhat rudimentary in the age of high-fusion propulsion, they are still necessary. Chemical propulsion ships are far cheaper and far easier to operate than expensive and complex high-energy spacecraft. They have more than enough delta-V to operate in small spheres. Additionally, chemical ships can be made much smaller than most nuclear craft and crewing requirements are less strict.

Electric Propulsion

The Whisper Burn Regime

Not every payload is in a hurry. Sometimes efficiency counts and operators are willing to wait for their cargo. This is where ions come into play. Like chemical rockets, ion engines have a long history. Probes and satellites were flying on ions even before the first Earth-Mars landings started in 2008. These systems are proven, reliable and low risk. Today, electric engines push millions of tons of cargo a year. Ions change the orbits of asteroids, push orbitals, fly satellites and steer cargo. The fuel types take a little bit more logistics, but are generally no harder to move around than the remaining fuels to be addressed.

Nuclear Fission Propulsion

The Atomic Burn Regime

The workhorse engines of the 21st and 22nd centuries. Fission reactors were initially brought to space to power large electric propulsion systems and the early orbitals around Earth and Luna. Of course it only took a few years for those pioneering Continentals to ask: What if we just use this thing to heat propellant?

Nuclear thermal rockets have swarmed interplanetary space ever since. Prior to the viability of low fusion, it was the best humanity had. True, the fuel is radioactive and much more difficult to manufacture, the exhaust plume is deadly and maintenance is a chore… but their continued use is a testament to how far the technology has come in three centuries.

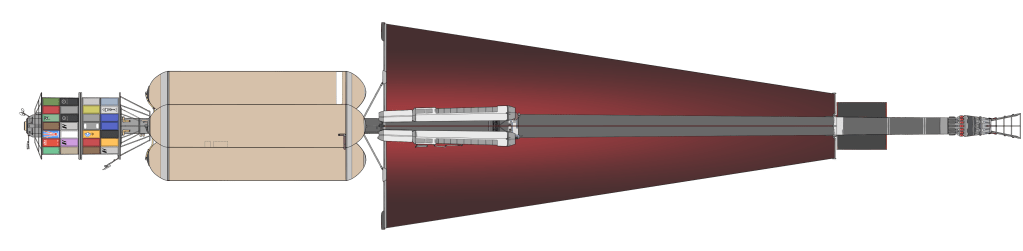

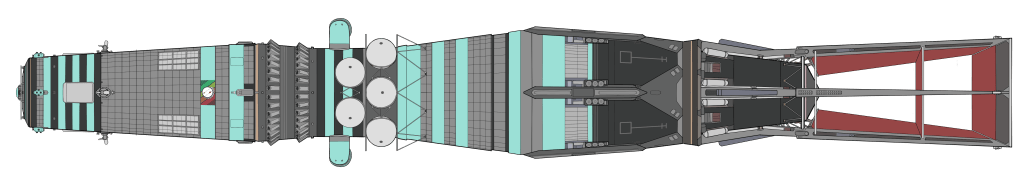

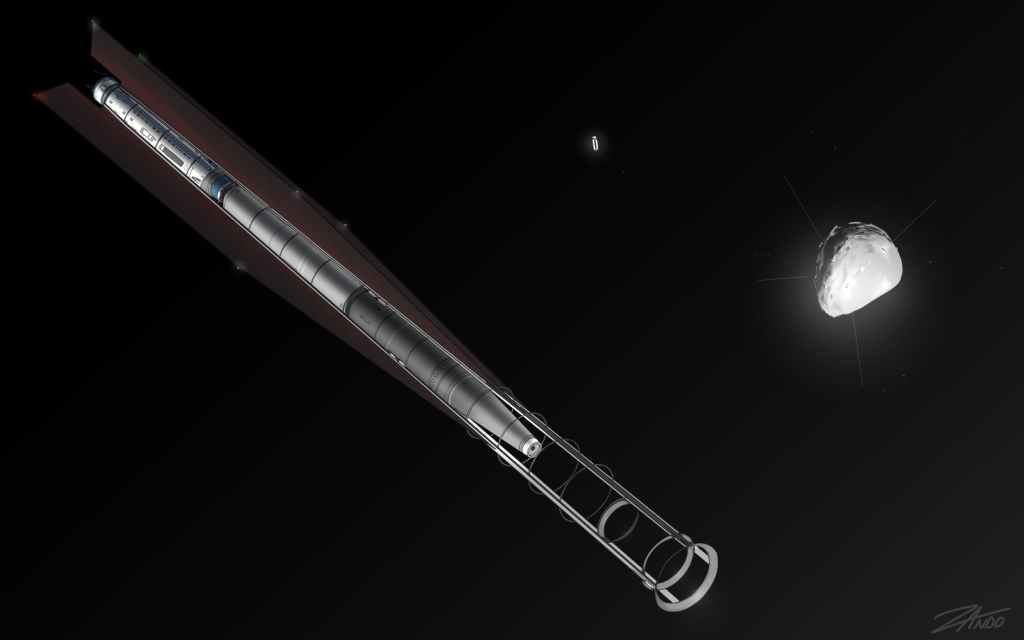

Nuclear thermal rockets can be identified by large radiators. The spacecraft will taper to fit within the radiation shadow cast by the reactor shielding at the aft end, usually resulting in a reverse arrowhead ship design. There may be shielding or spacers between multiple motors. All docking equipment will be on the forward end of the spacecraft, deep within the radiation safe zone and directly opposite the engines.

Nuclear Fusion Propulsion

The Neutron Burn Regime

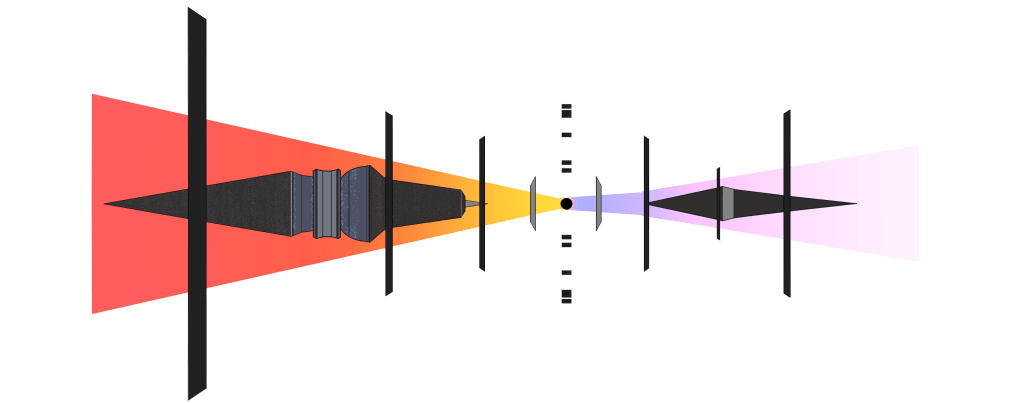

Low Fusion

Also known as lantern drives, fusion motors have been a common sight in the solar system since the mid 2100s. This form of propulsion utilizes the energy released from the fusing of atoms. Confinement is key in this technology, as the temperatures and plasmas involved were a problem during development. Magnetic and inertial confinement systems are used to control and direct the star-temperature exhaust of these rockets. Thankfully, this technology truly unlocked the solar system, permitting the vast and continuous flow of material and minds throughout human space.

Low fusion spacecraft can be identified by their magnetic nozzles, tokamak fusion reactors or laser ignition batteries. Usually these ships have dense reactor sections and much less dense exhaust sections. Like fission rockets, the spacecraft will be designed to remain within the radiation shadow of the drive shielding, often resulting in reverse arrowhead shapes.

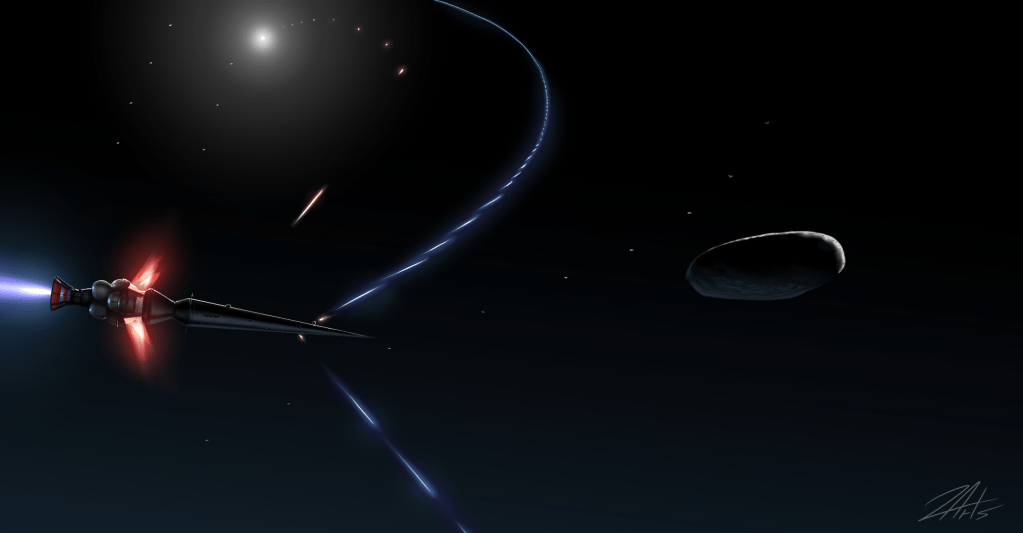

High Fusion

Bright drives. In the late 2100s, a breakthrough in confinement technology and spin polarization resulted in much higher efficiency fusion rockets. While not quite the torch drives of ancient fiction, these newer high fusion ships still provide a vast improvement over early fusion propulsion designs while still utilizing the same fuels. However, what benefits were gleaned in performance were paid for in complexity and operations cost. High fusion spacecraft are typically larger, very complex and enormously expensive to operate. Much like the supersonic travel debates of 21st century Earth aviation, sometimes the fastest option simply isn’t the most cost effective and cheapest. Today, high fusion propulsion remains the application of government entities, military function and specialized cargo and passenger transport.

A high fusion ship can be identified by their magnetically confined rocket engines, a lattice rocket nozzle with magnetic coils mounted with blade shields and very high energy radiators. Thermal control requirements are very demanding on these spacecraft, resulting in large, glowing wings of superheated droplets or even dusty plasma radiators. But the light of thermal control systems is dwarfed by the starlight exhaust of these drives. A high fusion plume can be seen from across the solar system.

Due to the destructive capability inherent in these spacecraft and the complexity of the technology that permits them, they tend to have strict crew requirements. Highly specialized operators are needed to fly and repair them, especially in deep space

Antimatter Propulsion

The Exotic Burn Regime

Antimatter propulsion was first demonstrated in 2283. Since that time it has been utilized in numerous experimental spacecraft, but never at scale. The challenges involved with the production, confinement and transportation of antimatter have remained a prohibitive roadblock to the technology. As of the 2370s, only the True Light of Sol are investing heavily in the production, storage and utilization of antimatter.

Ergo Propulsion

The Relativistic Burn Regime

??? ??? ??? ??? ???

Ship Types

Over the centuries, specific roles have developed in ship design, catering to the operational needs of spacefaring entities. The following list is not all inclusive. There are many roles in which some ships might overlap. The terminology is listed in Angli-Continental, but many ships are described in different languages, especially considering many of these ship roles evolved in places where Angli-Continental wasn’t the primary dialect.

Passenger Transport

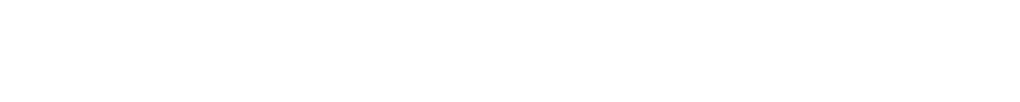

Liner – Large, fusion propelled, interplanetary passenger craft. What differs liners from most other passenger ships is the interplanetary aspect and the implied use of stasis. To remain economical, liners usually carry more passengers than they can keep awake.

A deep space passenger liner

Gasliner – Airships. Lighter-than-air transports that have been used on Earth, Titan and within many orbitals.

Airliner – A type of heavier-than-air craft that operates on Earth. In the pre-impact era, they crowded the skies by the thousands. Today, they’re a somewhat common method of connectivity across the fractured firstworld.

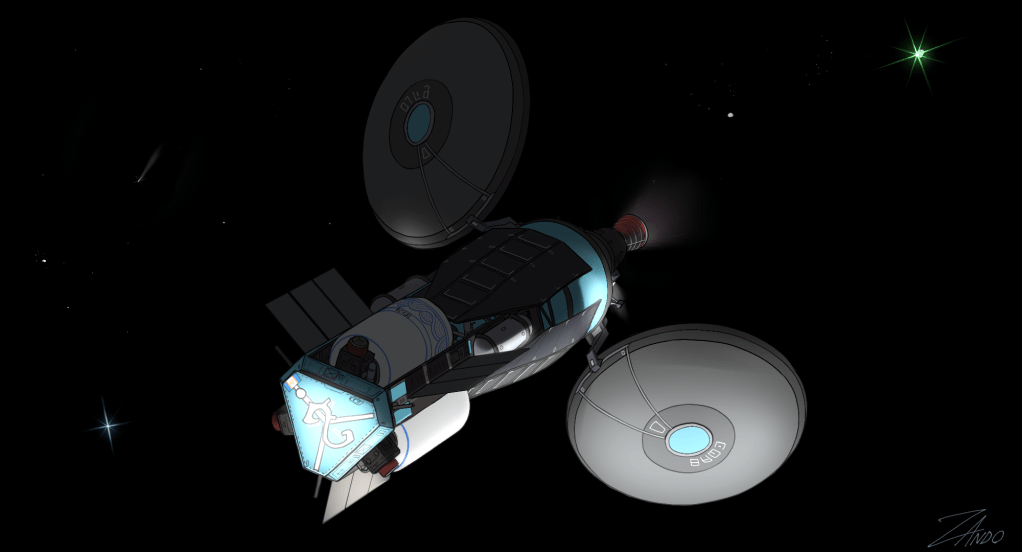

Oriole – Beam riders, spacecraft with fibrous wings or lensing rigs to collect laser light to use in propulsion. These are most famously flown in the Saturnian system. Historically, they have been used to transport passengers, but cargo and multi-use variants exist as well.

A Saturnian oriole in flight

Albessig – A balloon-to-orbit stage. These craft carry themselves through a chunk of Titan’s atmosphere before igniting their orbital rocket. In some designs, the rocket stage and balloon stage are separate vehicles.

Lielieo – A winged version of an Albessig. Mostly used on Titan, but similar types of craft have seen use on Earth.

Cargo Transport

Hvalie – derived from Norwegien hval, “whale.” A nuclear, interplanetary, bulk cargo pusher. Relatively cheap compared to high fusion craft, these vehicles make up the backbone of the interplanetary “fast cargo” economy.

Shinve-hvailes – Neobosti shinve, meaning reflective. A name for nuclear cargo pushers that can also take advantage of beam networks.

Barge – An affectionate Continental term for uncrewed, ion driven, bulk cargo spacecraft. Usually, these are little more than a propulsion section attached to cargo. Barges make up the bulk of the interplanetary “slow cargo” economy, where resources and goods sometimes ship decades in advance.

Rodetck – A ship designed for nuclear fuel transport. Often times this doubles as a service craft or a sort of tanker. Some variants even have fuel reprocessing capabilities.

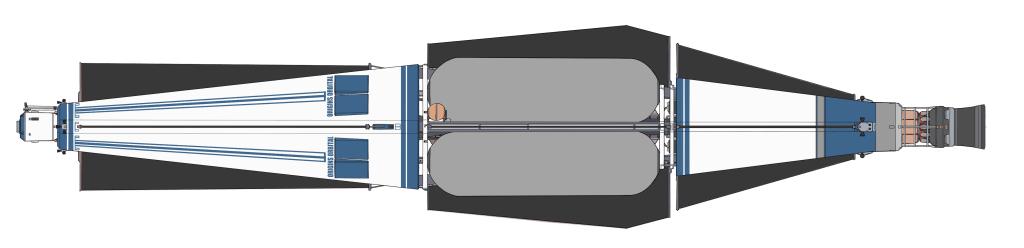

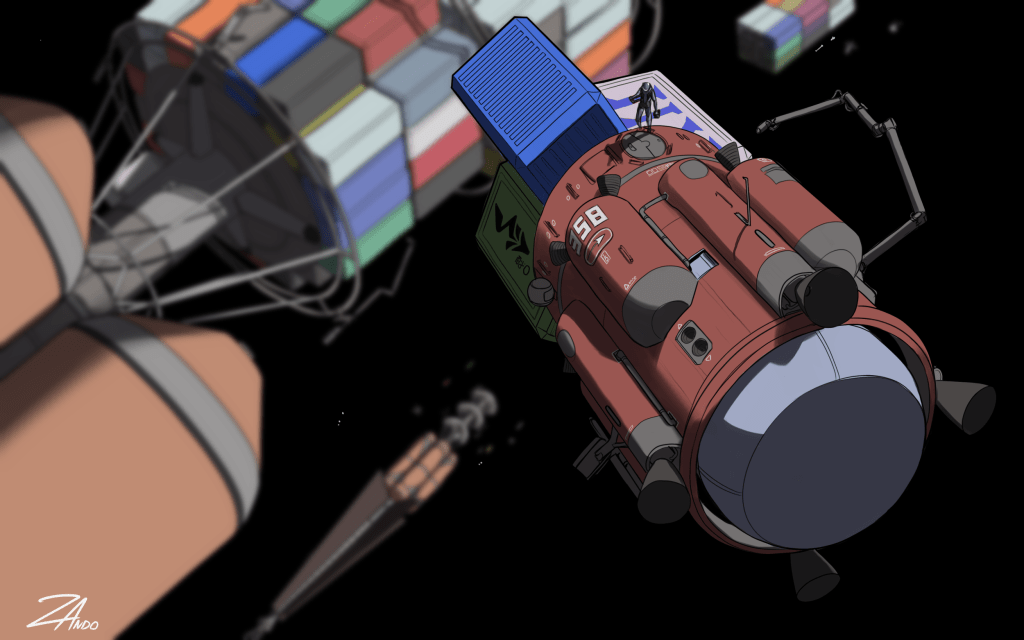

Lighter – Effectively a cargo shuttle. Lighters complete the cargo chain from large ships to their delivery points and visa versa.

A cargo lighter

Tug – A small spacecraft used for moving cargo (or other spacecraft) in the vicinity of orbitals or planets. Sometimes they are crewed, other times they are operated remotely. Small tugs might be fully autonomous.

Shuttles and Connectors

Sparrow – An Angli-Continental word for a small Earth bird. Describes the original brand of ship shuttle that grew to immense popularity in the late 21st century. Specifically, a sparrow is a small passenger spacecraft that is carried by much larger (often interplanetary) spacecraft.

Siftet – A play on the neobosti word for “patience”. An electric drive shuttlecraft.

Light Shuttle – A term describing a shuttle for less than 10 people. Often these are very specialized or privately owned.

Regional Shuttle – A catch all term for a shuttlecraft that operates within a single major sphere. A regional shuttle could mean a passenger spacecraft that only operates between orbitals within Ceres sphere of influence, for example. This starts to get misconstrued when referring to much larger, planetary spheres.

Heavy Shuttle – A spacecraft that moves hundreds of people.

Cascadie – Aerobrake shuttlecraft. Typically these aren’t surface landers, but passenger transports that make use of atmosphere to decelerate. Such craft exist around Titan, Mars and Earth spheres mostly.

Landers

Lunabbi – Catchable spacecraft. Lunabbi was the original brand name of a popular moon lander design that could be captured by a tower on descent, then safely lowered to the surface without using it’s own engine. The name was adopted for use in similar designs across the solar system.

Lem – A vacuum lander. The term apparently comes from a series of landers used by the Continentals in early spaceflight. Now it refers to almost any spacecraft that can soft land on a body with no atmosphere.

A lem-type lander touching down at an unprepared landing site

Duster – A whisper-drive lander designed for repeated landings on very low gravity bodies. Dusters ‘hop’ or float their way around the exteriors of large asteroids and small moons. These are mostly useful in places where the gravity is so low, it’s difficult to land a traditional craft. Some dusters are so gentle that they have exterior seating for spacewalkers.

Aux Oriole – A beam-rider lander, obviously only useful at spaceports with nearby beam stations.

Fuelers

Tanker – Effectively a mobile refueling station. Usually little more than propellant storage with guidance, maneuvering and a very efficient engine. Sometimes they work with drones that assist in refueling.

Glowtug – Similar to a rodeckt, but specifically designed for nuclear refueling. Despite the name, glowtugs are not tugs.

Military/Weaponized

Erakker – Neobosti verb for stabbing or puncturing. A large attack spaceframe, implied to be interplanetary. Usually these are high fusion ships with extraordinary amounts of armament. The idea is to penetrate an enemy sphere of influence for a devastating flyby with very little support from other craft.

Fracter – Neobosti verb for a darting/zipping. A fast attack, defensive spaceframe. Usually, synonymous with the low orbit interceptor role. Spacecraft designed to deploy in numbers, intercept SOI invaders at short notice and accelerate quickly to do so.

Phancifacta (Phancer) – Neobosti, roughly interpreted as defaming ghost, but ghost in Neobosti can also imply someone who hides. A crewed electronic warfare spaceframe, usually one that is used offensively.

Cakktor– Neobosti verb for destroy. The descriptor originated in the Phobos Crisis to describe a strategic missile craft. In the modern era, the term applies to standoff missile carriers.

Takktor– A small, armed spacecraft for enforcing police actions. Military versions may perform orbital denial roles in small spheres of influence.

Anti-fracter – A spacecraft designed to defeat fracters. Usually this involves a laser-armed ship that can pick off lots of incoming missiles or the fracters that launch them.

Jammer – Plainly, a craft designed to jam incoming threats.

Military Other

Thresher – A crewed spacecraft designed to enforce diplomacy. Typically, they double as signals intelligence platforms. The name is a play on Continental-Angli and Theoparti. The Angli noun thresher describes a species of Earth fish that resembled the first models of spacecraft in the role, and the Theoparti word threshki which can be interpreted as mischievous.

Trektor – A dedicated signals intelligence and communications node. While these ships are usually crewed, they may act as an expeditionary control node for vast satellite constellations.

Breacher – A catch-all term for any spacecraft that forcibly enters orbitals. Invading orbitals has always presented a challenge for military planners. If a faction controls the orbital’s spaceport, they’re effectively invulnerable. Destroying orbitals is unprecedented, and because most large orbitals can make themselves somewhat self-sustaining before they starve or suffocate, a siege could last for years. Therefore, breachers are the answer to the question: “What if we made our own way in?”

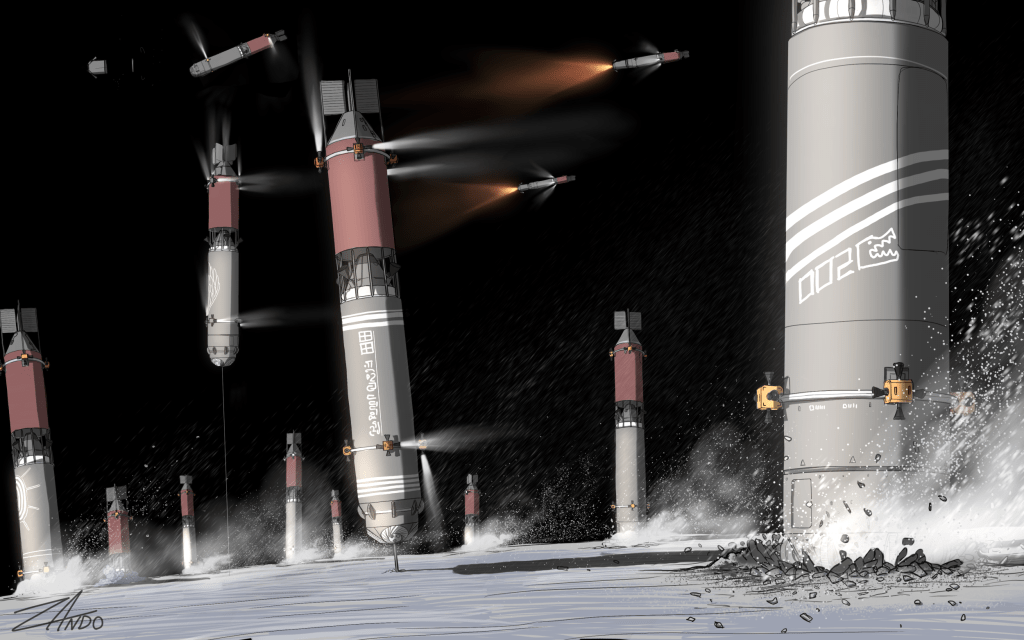

Breachers boring into the skin of an orbital

Crew

Automation runs heavy in modern spacecraft… but some still rely on small crew components. With stasis technology, even a massive erakker might only need a crew of 4-12, while smaller non-nuclear ships may only require 2-3. A piloted shuttle might not even require more than one individual.

Pilots

Pilots are responsible for flying the spacecraft. The vast majority of the time, this does not involve having human hands on the controls, but rather managing the complicated automation that controls the flight systems. Many spacecraft, (especially large, expensive, complicated ones) have failure modes that rely on the manual input of a pilot.

Beyond the systems requirements, a pilot may also be required for onboard leadership. While the term pilot refers more to the expertise, the term spacecraft commander refers to the authority. Even if there are multiple pilots on board, there will legally be only one spacecraft commander, and they are the legal signature authority for that particular spaceflight, be it military or civilian, in the laws set forth by the Space Security Guild.

Astrogators

Astrogators are sometimes used to operate spacecraft navigation systems. Qualifications normally include certification in advanced orbital mechanics, far beyond what might be expected of a lone pilot. Astrogators are less common in the orbital environment. More often, they are employed on large, deep space ships with more complicated computers.

Much like with pilots, there are large, expensive spacecraft that have redundant failure modes that include the use of human astrogation, especially when it comes to verifying computer generated astrogation solutions and flight planning.

In the coming decades, crewed interstellar craft are expecting to have entire teams of astrogators.

Technicians

Perhaps the most common crew position amongst spacers, technicians are responsible for fixing and maintaining spacecraft systems. This is truly the realm of human labor in spaceflight, as no one has yet invented a spacecraft that can run indefinitely. Some examples of technician specialties include:

- Reactor/Powerplant

- Propulsion

- Communication

- Sustainment and Life Support

- Avionics/Astronics

- Fuels

- Hydraulics

- Automation

- Robotics

- Thermal Management

- Structures

- Munitions

Sensor Operators

Spacecraft automation is pretty good at detecting things, but not always knowing where to look or what to look for. On crewed platforms, therefore, it is sometimes prudent to have a specialist on board who can make real time decisions with the sensors and troubleshoot them when they misbehave.

Combat System Operators

Sometimes you need a finger on the trigger in real time (though it’s more of a sequence of fire control routines). Relying on remote controllers, often light minutes or light hours away, simply doesn’t cut it in modern warfare. Autonomous weapons systems have their place, but when it comes to the moon-destroying potential of modern warcraft, most nations prefer not to leave decimation in the hands of automation. A human operator normally has control over redundant safety measures, weapons programming, munition management and targeting protocols. The weapons themselves, in most circumstances, are completely automated. No physical trigger required.